Minnie’s husband George mentions football and golf in his sixth letter from the front. I know from elsewhere that he was also a crack shot. He was clearly a sporty person.

But what did George mean by football? And what would have been his experience as a Dewsbury lad?

George was born in 1868.

At this time, Rugby was still mainly an upper class sport. Rugby’s increase in popularity in the working classes came with the education of the sons of mill and pit owners at private schools, accompanied by a boom in industry and more free time for the workers.

The first clubs in Yorkshire (Bradford, Hull and Huddersfield) had only been set up around 1863. They were founded by old boys of Bramham College near Leeds the sports ideology of which was ‘muscular Christianity’. Charles Blakeley, George’s father, had been a pupil at Bramham College.

Dewsbury Football Club was inaugurated in 1875 as Dewsbury Athletic and Football Club when George was seven years old. It secured its grounds at Crown Flatts the following year.

The Rugby played at this time was amateur. The public school ethos of playing for love and honour ruled the day. Professionalism was abhorred.

Here’s a clip from the Huddersfield Chronicle of 19 January 1877 p4. It shows the Dewsbury team line up:

This was a local team. Eight of the surnames of these players appear on Minnie Kirk’s family tree. There’s an even closer connection. Minnie’s grandfather (Edward Hemingway) and her great uncle (Thomas Spedding) were in partnership at Aldam’s Mill with Mark Newsome the elder. Three members of the team were the sons of these gentlemen. It was also a young team. Alfred Newsome was 16 years old, his brother Mark was 18, and Robert Spedding was 21.

For posterity, here’s a clip, courtesy of Stuart Hartley, which shows Crown Flatts and the signature of W B Adkin, one of the players:

Here’s a later clip:

This is from the Leeds Mercury of 12 October 1886 p7. George was 18 years old. Mark Newsome was now president and former captain of the club and was aged 27 years. Dewsbury’s team is no longer quite so local. The clip refers to two players from Wales.

The background to this is that professionalism had been creeping into the game. Payments in kind were becoming popular, as were inducements to players to leave one club and join another, the inducement perhaps being a better paid job in the new area. The two Welsh players, William ‘Buller’ Stadden and Angus Stuart, had in fact, been given employment in the mill belonging to Mark Newsome’s father. Cardiff, naturally, disliked this poaching of their players, and thus their accusation that Dewsbury was countenancing professionalism.

The new rules to which Mark Newsome refers were a clamp down on professionalism. They stated that payments were to be limited to expenses only, and ‘those in authority shall have power to suspend any professional or any club employing a professional, or which plays a match with any organisation employing a professional..’ (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 11 October 1886 p8).

In his excellent book Rugby’s Great Split, Tony Collins furnishes more information. Stadden and Stuart stated that they had signed for Dewsbury because they were out of employment, and had made friends in Dewsbury. This may, of course, have been the case. However, it appears that Newsome was pushing the boundaries of amateurism and getting away with it.

Mark Newsome is something of an enigma. He voted against benefit matches to aid striking miners in West Yorkshire in 1893, but he voted, in the same year, for ‘broken time’ payments, by which working class players would be compensated for time lost from work to play rugby. The vote went against broken time payments, and this was significant in the lead up to the ‘Great Split’ of 1895, when 22 northern teams left the Rugby Union and formed their own Northern Union (later to become Rugby League with different rules including reducing the number of players from 15 to 13).

Although he had voted for broken time payments, Newsome did not wish Dewsbury to join the Northern Union. His vision was of rugby as it used to be, that is a game of the upper classes. In fact, Dewsbury stayed in the Rugby Union, but popularity declined as the best players moved elsewhere, and in 1897 the team adopted soccer. It took the formation of a new club in 1898 for Dewsbury to join the Northern Union.

Mark Newsome would in time be made chairman of the Rugby Union.

Mark’s father, also called Mark, was a wool manufacturer as was his grandfather, Thomas. Mark Junior was educated at William Jefferson’s school in the Horsefair at Pontefract, as was his brother Alfred. Mark’s son, Guy, went to Rossall School. It still exists. According to its website, Rossall was ‘widely considered to be in the top 30 public schools in the UK and by the end of Queen Victoria’s reign…enjoyed a reputation as the Eton of the North’. It’s right on the coast at Fleetwood, north of Blackpool. Would that we all went to such a school. It’s website is proud to mention Peter Winterbottom , England rugby player, as an alumni. These schools certainly played amateur Rugby.

Mark Newsome was a public school alumnus, but he was also a business man, and son of business men. This, I think, helps us to understand what seem to be some conflicting decisions. He wished to belong to the amateur organisation, but also wanted to improve his team by importing better players.

Here’s another clip. It’s from the Yorkshire Evening Post of 27 September 1913, p5:

This was after the split. Dewsbury was part of the professional Northern Union and immune from Rugby Union laws. it could take players from where it wanted, and reward them appropriately.

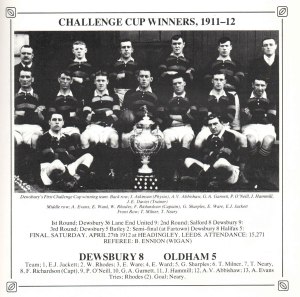

As might be expected, the line up no longer had recognisable Dewsbury surnames. Here’s the team in 1911-12 from The Official History of Dewsbury Rugby League Football Club, (compiled by Scargill, Fox and Crabtree):

George was 45 years old at this time. He’d seen the transition from amateurism to professionalism, and from a team of people he knew to a team of celebrities.

How did all this play out at a personal level?

Bradford born Mick Martin paints a credible picture of Rugby in a Yorkshire town at the time of the split in 1895. His play, Broken Time is set in the fictional West Broughton. It premiered in Wakefield in 2011.

I would love to see this play, but have had to content myself with reading the script which charmingly captures our Yorkshire dialect and sense of humour. It’s an exploration of vested interests.

The gentlemen members of the team, who played rugby at their private schools, have their separate changing rooms, as well as first class travel and hotel accomodation for away games. They have a belief in honour, glory and empire, and wish to keep the sport amateur.

The mill and pit workers are less well off, and appreciate the perks of the game which include some money and a ‘leg of lamb dropped round the house for Sunday dinner’ when they win. They accept, but harbour some resentment towards their ‘betters’ especially against a background of wage cuts and a situation where an injury sustained in a rugby match could result in a player and his family becoming destitute.

Their main resentment is for the Welsh player recruited by their mill owner boss who is set up as landlord in a public house to give him a living. I don’t know on which town the author was basing this story, but it mirrors the Dewsbury situation.

Conflicting interests come across strongly in the play. The mill owner in particular is in a paradoxical position, and puts me in mind of Mark Newsome. He is a gentleman with a gentleman’s education, but he is also a business man. He wishes to obtain the Welsh player for his team, but wishes to deny that any payment has been made in order to continue to belong to the amateur Rugby Union.

After the Great War started, things continued as normal for a while, but as people realised that it was not going to be over quickly, and as casualties began to arrive from the front, rugby playing was cut back significantly. Many players joined up, and later were conscripted. Informal competitions did continue, however, and Dewsbury won the unofficial championship title in the 1915-16 and 1916-17 seasons. Dewsbury manufactured woollen cloth for uniforms, and thus had a thriving population to attract players, and had the crowds to support the matches.

Teams were set up in the forces, and these were Rugby Union teams in the main, although they took both kinds of players. Active military recruiters would pursue known players for their army teams. In France, George is more likely to have seen soccer. This had simpler rules and was easier to organise by an army away from home. Moreover, it didn’t have the class connotations of rugby, and could be played comfortably by men and officers together. Outside the north of England, rugby was considered to be a posh man’s sport.